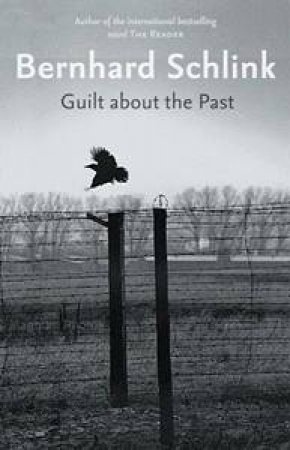

It therefore behooves Styron to place a typical (i.e., Jewish) victim of the Holocaust at the center of his tale. The difference is that Hitler did not deliberately set out to totally eradicate Poles along with their religion and culture from the face of the Earth as he did with the Jews. It is true, she said, that 75,000 Polish Catholics were murdered at Auschwitz, and the suffering and death of those Poles was no less horrible than that of the death camp’s Jewish victims. Ozick found fault with Styron for making the heroine of his novel a Polish Catholic rather than a Jew. Ozick’s only examples of works that cross the line into imaginative irresponsibility were Holocaust novels: “Sophie’s Choice” by William Styron and “The Reader” by German writer Bernhard Schlink. It may be that in Ozick’s view other historical events beside the Holocaust require restrictions on the fiction writer’s imagination, but these other events did not come up. Ozick, a highly respected writer of short stories, novels, and essays, is the author of “The Shawl,” “The Pagan Rabbi and Other Stories,” “The Puttermesser Papers,” and, most recently, “Heir to the Glimmering World,” the story of a Jewish immigrant family in New York who are supported and exploited by a character based on Christopher Milne, who was himself the model for his father A.A. 28 talk “The Rights of Imagination and the Rights of History.” The lecture, which honored the memory of novelist Saul Bellow, was co-sponsored by the Center for Jewish Studies, the Department of English and American Literature and Language, and the Alan and Elisabeth Doft Lecture and Publication Fund. This was the argument presented by writer Cynthia Ozick in her Nov. The exception to this rule is when a fiction writer takes on the Holocaust. The writer of fiction may alter and distort reality in any way he or she pleases, as long as the result possesses a consistency that allows readers to suspend their disbelief and accept the imaginative world the writer has created. Cynthia Ozick took fellow writers William Styron and Bernhard Schlink to task for their fictional treatments of the Holocaust in, respectively, ‘Sophie’s Choice’ and ‘The Reader.’ (Staff photo Jon Chase/Harvard News Office)

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)